It's an Uphill Battle but Somebody's Got to Do It When All Else Fails, Preserve Historic Time and Place on Paper |

The reason the Edison National Historic Site (based in West Orange) glosses over

so much of Edison's daily life is because they have no interest in learning about

the town where he lived. It's been a bone of contention the author has had with

that site and it's a valid one considering that his grandfather worked as one

of Edison's personal messenger boys and countless other family members worked

in the Edison factory just like so many other West Orange residents. Dandola

often cites that Edison's winter getaway in Fort Myers, Florida, does a much

better job of tying the inventor to his surroundings. "Local historians are usually brushed aside as being too annoyingly prone to minutiae," says Dandola. "That's often very true but minutiae should still be examined and it can ultimately prove invaluable." A case in point is that Dandola also knows where the horses were rented for the chase scene in The Great Train Robbery because a descendant of that rental source went through school with Dandola's great-aunt and later wound up being Dandola's neighbor. West Orange was once the kind of town where people stayed for generations. It no longer is. "Properly interpreted, it's the little things that make up an accurate whole," he says. "Knowing where the horses came from, how they got to the shooting location, and why that was the shooting location paints a very compact small town picture of how movies began. Not knowing the town and its layout is why the Edison Historic Site and countless other sources get the filming location wrong." An accurate whole is what should be truly important. Unfortunately nowadays, so-called historians instead reach for easy straws and make up fallacious points of importance. A case to illustrate that recently came to light. West Orange has been infamous for knocking down old buildings. Laughably, it wasn't until all the damage was done that an historical preservation committee was created. "The town has never put skilled or talented people in place who understood that buildings can be revitalized. They've almost always knocked down rather than reimagined. There's never any attempt or mandate that the new must blend in with the old. At some point, it's too late." Dandola is very serious about this subject. "West Orange no longer has any historic character. There's few old-timers left and the new-comers don't care. A singular building left over, standing willy-nilly, doesn't lend character anymore than adding up the number of trees in town equates to contiguous open space. The latest lunacy is that they want to preserve one of the few older buildings—a rather nondescript one built round about 1900—and they're touting that the reason is because of the brickwork on its facade. The brickwork is the same as any number of buildings—both businesses and apartment houses—built during that time period. It's not exotic but they have no local reference. Granted, it was done when craftsmen took pride but it's everyday in style and workmanship. I guess when you've knocked down everything else, what's left is considered rare even though it's mundane." Usually someone at this point pipes up to offer, "But it's like that everywhere." Dandola's response: "That is emphatically not true. I can say that because during my career, I've lived in other states and quite a few different countries. What it boils down to is whether there's interest and pride in surroundings and what those surroundings give back in return." It's the very reason why Dandola has sought to preserve West Orange as it once was in his novels. He's been rewarded with praise that his writing conjures up imagery, atmosphere, and blue-collar charm—things which no longer exist there. Dead During Intermission, the tenth West Orange-based mystery, is set to debut in mid-May. |

Copyright © 2023 John Dandola, Ltd. All rights reserved. |

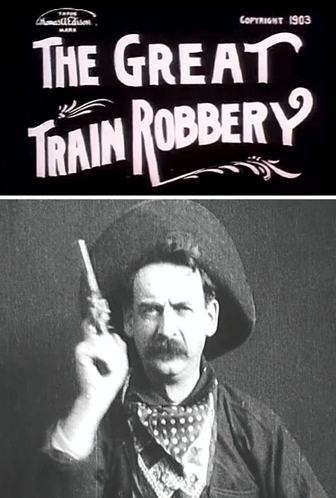

John Dandola's newest 1940's mystery novel, Dead During Intermission, contains an extensive passage of dialogue delivered by Thomas Edison's youngest

son, Teddy, during the course of a movie premiere. That passage reveals the locale

of where they filmed the chase and shootout in 1903's silent film, The Great Train Robbery. It's something that's been reported incorrectly for more than a hundred years.

If you want to know where it was filmed, as they say on the talk-show circuit,

you have to buy the book. But how and why Dandola would know such a thing is what's

most interesting. All of the novels in his Dead series are based entirely or in part in his hometown of West Orange, New Jersey,

and The Great Train Robbery was filmed there. To repeat an old joke: the movies' first Western was an Eastern. "Local history is its own specialization," the author comments. "You need to know a great many things in order to make correct interpretations. All too often, historians read about a place and make assumptions or reach conclusions which aren't entirely true. I know firsthand that when doing research, I first gather information and I then visit where something or other happened. Often, the information, although correct in a general sense, is incorrect when it comes to the details of distances and topography. Those two things can put a whole different spin on the truth." |